Permalink |

Add to

del.icio.us |

digg

Post tags: Bananas, cut food waste, freezing vegetables, how to keep bananas from ripening, how to keep fruit fresh, how to keep vegetables fresh, how to store bananas, how to store berries, how to store fruit, how to store fruits and vegetables, how to store ripe bananas, how to store vegetables, keep your fruits and veggies fresh longer, keeping berries longer, keeping fruit fresh longer, storing berries, storing produce, storing vegetables, sustainable food, what to do with ripened bananas

Unilever's Open Innovation team launched a new online platform which offers experts the opportunity to help the company find some of the technical solutions it needs to achieve its ambition of doubling the size of its business while reducing its environmental impact.

Unilever's Open Innovation team launched a new online platform which offers experts the opportunity to help the company find some of the technical solutions it needs to achieve its ambition of doubling the size of its business while reducing its environmental impact.

The RIBA Guide to Sustainability in Practice is an invaluable new sustainability guide for architects, written by architect and sustainability expert Lynne Sullivan OBE.

The RIBA Guide to Sustainability in Practice is an invaluable new sustainability guide for architects, written by architect and sustainability expert Lynne Sullivan OBE.

Elon Musk's Tesla Motors isn't just an electric car company--it's perhaps the greatest test of Silicon Valley's innovation model. And now is do-or-die time, when everything is riding on a new $50,000 sedan.

Photo by Joao Canziani

Photo by Joao Canziani

When Tesla Motors moved into its new Palo Alto headquarters in 2010, CEO Elon Musk raised a flute of Champagne and toasted his cheering staff. In a light, elegant accent--a remnant of 17 years growing up in South Africa--Musk said to the crowd: "Here's to creating the greatest car company of the 21st century, and to making a real difference in the world, and to moving us off fucking oil as fast as possible." You can actually watch Musk doing this if you're curious, about 80 minutes into the documentary Revenge of the Electric Car. But, in fact, this is the kind of thing that Musk says all the time, in television interviews and at technology conferences, and he's been saying it about his firm even before people began paying much attention. Back in 2006, for instance, two years before Tesla started deliveries of the sporty $109,000 Tesla Roadster, its first (and so far only) model, Musk happened to write on his blog that the master plan for his company was fairly simple:

1. Build sports car 2. Use that money to build an affordable car 3. Use that money to build an even more affordable car 4. While doing above, also provide zero-emission electric-power generation options

What rankles Musk is how often his master plan gets ignored. Sitting at his desk in Palo Alto on a January morning, Musk tells me he has been repeatedly criticized for being an elitist--"one who thinks there's a shortage of sports cars for rich people." He seems resigned to the fact that the proof that he is not a snob will only arrive in good time. Soon enough, Tesla will demonstrate to the world that its products are not for millionaires but for everyone. And the same kind of proof that silences the critics who cry elitism will likewise burn the stock-market speculators who are betting big money that Tesla's failure is imminent. "We're the third-most-shorted stock on the Nasdaq," Musk tells me, looking somewhat incredulous. Then he laughs. This actually cheers him up. "All I can say is if you're shorting Tesla at the end of this year, it's going to sting," Musk says. "It's going to sting a lot."

Whether this turns out to be true or not, Tesla Motors is now poised to build its first semi- affordable car, which puts it between steps one and two of Musk's master plan. By July, the company says it will begin delivering its new Model S sedan, a fully electric vehicle that's being manufactured at Tesla's new factory, in Fremont, California. The Model S seats between five and seven passengers; it will start at about half the price of the Roadster--$49,900--placing it in potential competition with a variety of so-called mass luxury cars like BMW's 5 series and the Audi A7. Another Tesla model, an SUV known as the Model X, was unveiled in early February and will likely hit the market sometime at the beginning of 2014, at prices close to the Model S. Yet further down the road, should Tesla survive and thrive, a prospect that is by no means certain, things get more interesting. Later that year, a third-generation Tesla Motors car will be unveiled. This is step three on the Musk master plan. The vehicle--it's not yet named--will be an affordable $30,000 car. It truly may be a Tesla for the masses.

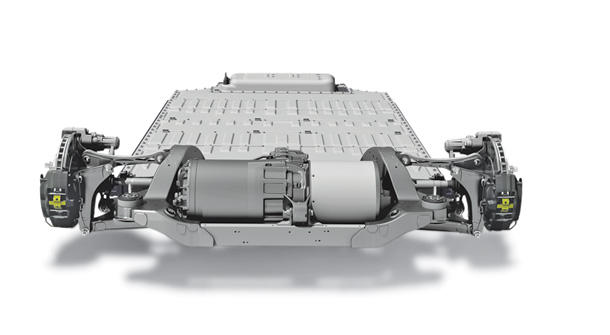

The bones of the Model S, with its battery-pack system hanging below. Photo by Joao Canziani

The bones of the Model S, with its battery-pack system hanging below. Photo by Joao Canziani

You might think of Tesla as a company that exists to sell electric cars. Yet after spending time with Musk, you begin to see that Tesla is not really a company that exists to sell electric cars. Rather, Tesla is a company that exists to overturn the entire global automotive infrastructure, an infrastructure that presently functions on petroleum and internal combustion engines but in Musk's belief will eventually, and inevitably, glide forth on exhaust-free electricity. To Musk, the most significant problem with this transition is that we don't know how fast it can or will happen. And this leads to other questions. How quickly will Musk be able to scale up his business to have an actual impact on the world? And when will his competitors--some of whom, Toyota and Daimler included, have paid Tesla hundreds of millions of dollars to build motors and battery packs for their own electric cars--get on board in a big way?

Tesla represents the most extreme test in modern history of the limits and capabilities of the Silicon Valley model.Another problem is that Tesla Motors is doing something hard. Not hard in the way that working day and night on a new website or a social-media launch is hard. What Tesla Motors is doing is hard in a way that makes your mind ache. The difficulty of the endeavor--making machines that are big, heavy, and incredibly complicated; making machines that require 1,400 employees to design, engineer, and manufacture; making machines that consist of thousands of parts, sourced from all around the world, that must work together flawlessly for years on end; making machines that must be regulated at every step for safety and emissions; making machines that traditionally have slender profit margins; making machines that use a radical new technology with a track record of only a few years; and making machines that in their electric incarnations have never appealed to a large market of buyers--explains why most entrepreneurs would rather start a business moving electrons around the Internet than within a car motor. If launching a major new automobile company is close to nuts--"probably the hardest thing in the world," as one auto analyst told me recently--then launching a major new electric automobile company is certifiable. You might as well light a bonfire in downtown Palo Alto and burn a billion dollars.

Tesla Motors almost certainly represents the most extreme test of the limits and capabilities of the Silicon Valley model of innovation. Musk's startup is built on a defiant and scrappy ethos, and it intends to demonstrate that a product that has long been the exclusive bailiwick of Detroit engineers can be made smarter, faster, cheaper, and more attractive by a bunch of guys in California, Musk included, who don't tuck in their shirts. Of General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler, Musk remarks, "I think the youngest of them is 90 years old." The most common refrain he's heard over the years is that Tesla can't possibly succeed because nobody has succeeded in nearly a century. Indeed, Tesla and Musk are frequently lumped with the upstart Tucker Sedan (launched by Preston Tucker; bankrupt 1949) and the insurgent DMC-12 (launched by John DeLorean; bankrupt 1982). "If I had a dollar for every time someone brought up Tucker or DeLorean," Musk tells me, "I wouldn't have needed to do a bloody IPO."

Did he know how difficult this would turn out to be from the start, I ask?

"Yes."

Was he surprised by how hard it actually was?

"No."

After a pause, he adds, "When we got Tesla going at the very beginning, if you asked me what I thought the odds of success were, I would have said less than 50%. I would have said that failure is the most likely outcome." But he would not say that anymore.

To put it starkly, the future of Musk's company now hinges on the success of the Model S. He has put all his chips on the table; his company has even suspended production of the Tesla Roadster for several years to focus on the new model. If the Model S has "hiccups," the term carmakers use to describe modest production glitches, it could likely get past them. But if the car has larger issues of performance, safety, or durability, it gets more difficult to see how Tesla could endure. Even with its alliances with other automakers, the company could be hundreds of millions of dollars in the hole. And Musk's public assurance of company profitability in 2013 would likewise be jeopardized. "It's a make-or-break product for us," J.B. Straubel, Tesla's chief technical officer, tells me one afternoon. The big car companies have a lot of models, he remarks, and success for them can be a game of statistics. Some models hit it big, and by doing so they compensate for models that tank. Tesla has no room for error. "We're very cognizant of that fact," Straubel says. "The Model S has to be better than all the other cars. Not just okay. Or else we've failed."

Straubel and Musk both work out of the second floor of Tesla's headquarters, in a gymnasium-size room where most of the company's business is done. Hundreds of staffers, hunched in front of computer monitors, sit crowded together. There are no cubicles; in the company's quest for efficiency, all the desks are Ikea tables. Musk, who goes to the office two days a week (he lives in L.A. rather than the Valley and spends a significant part of the week at his other big startup, SpaceX), sits to the side of the big room, a few feet away from Straubel, at a polished wood desk. Other than a MacBook Pro, a water bottle, and a mug of coffee, Musk's desk is clean. "These days, I work probably 85 hours a week, maybe 90," he tells me. While he's now at the office part-time, he says he still manages the company 24/7 and that no nuance of engineering and design is beneath his scrutiny. I heard this from a half-dozen others at Tesla too--that Musk's involvement verges on that of a Jobsian obsessive, which is arguably not a bad thing when your company has to build something that is essentially flawless.

How the Model S Moves

1. BATTERY Like all electric cars, the Model S's motor is fueled by a pack of lithium-ion batteries--in this case, a flat pack of them embedded underneath the floor of the car. The lowest-capacity Model S battery powers the car up to 160 miles per charge--at least 60 more than most competitors'. That may increase the battery's life span, because fewer charging cycles are needed.

2. MOTOR When you press the car's pedal, you increase electricity flow from the battery to the motor. Unlike a gas-powered internal combustion engine, the Model S's motor is fairly simple: The electricity creates two magnetic fields, causing a magnetized component to spin around, which creates the mechanical energy that activates the hardware that turns the car's wheels.

3. SYSTEM While a gas-powered engine system has many moving parts, electric cars have relatively few--no fuel lines, tanks, or exhaust--meaning the car is more efficient in using energy. About 75% of the battery's energy goes into moving the car; in a gas-powered car, that number is about 20%.

4. BRAKING When you hit the brake in a gas-powered car, momentum and energy is lost as heat. In the Model S, something different happens: The motor becomes a generator, spinning in the opposite direction and turning the excess mechanical energy back into electricity that partially recharges the battery.

--Lindsey Kratochwill

Downstairs from Musk's office is Room 24M, a cavernous, high-ceiling garage brightened by hanging fluorescent lights, where the company's new cars get evaluated. During my January visit, most of the spots here are taken up by what's known as the Model S "beta" fleet--several dozen early-production, not-for-sale Model S cars, all painted black and all given a number. Each beta is for a different type of testing and data collection--on brakes, suspension, noise and vibration, crashworthiness, and so forth. Tesla is not letting any outsiders drive the vehicle yet, but Ali Javidan, who runs the garage, offers me the shotgun seat in beta car No. 24.

"The interior isn't finished," he says as we pile in, but everything else is pretty close to operational. There is no way to turn a Model S "on"; you merely need a key fob in your pocket and a sensor allows you to drive once you're settled in. We head out of the garage and up into the hills, on the winding roads above the Tesla offices. The car is sleek and smooth. And whisper quiet. One of the hallmarks of a well-engineered electric car is its torque--that is, what drives its acceleration. In part this is because electric-vehicle (EV) technology is significantly more efficient than a gas engine. I tell Javidan the car feels fast, and he looks at me quizzically. "I only had the pedal down a quarter of the way," he says. So he floors it, and my head immediately snaps back, not unpleasantly, against the headrest.

To understand why the Model S is innovative as well as risky, a quick gearhead primer is useful. Electric cars are in certain aspects much simpler than gas cars. There are fewer moving parts, and there's no engine of any kind. Electric cars have a motor, which in the Model S is fairly small--about the size of a watermelon--and is located between the back rear wheels. The motor runs on electricity stored in lithium-ion cells, thousands of small batteries, that in this particular model are arranged in a rectangular "flat pack" compartment that in effect forms the floor of the car. The software of the car is in an essential component too; through something called a drive inverter, it regulates how stored energy in the battery pack is used by the car's motor.

How you know you're looking at the Model S--or any electric car--from above: There's no tailpipe. Photo by Joao Canziani

How you know you're looking at the Model S--or any electric car--from above: There's no tailpipe. Photo by Joao Canziani

Musk and others at Tesla contend that the Model S may be the first mass-produced car ever designed, from the ground up, with the specific purpose of being an EV; therefore any design conventions of gas-burning technology have been avoided. (The Nissan Leaf is an adaptation of the Nissan Versa.) On a more granular level, though, it's not a simple matter to convey how Tesla's technology may give it a comparative advantage over the competition. The company has more than 300 patents on its technology, all of them highly technical, and in addition has a fair amount of proprietary engineering. In the most general terms, it's probably fair to say that the company's expertise resides in how it has designed the circuitry in its large battery pack, how it cools those batteries, and how its sophisticated software regulates the power flow between the battery pack and the motor. The software especially, which can translate into large efficiency gains for a car, may be Tesla's biggest advantage. Straubel notes that one benefit of being located in the Valley, as opposed to Detroit, is that it offers the company a huge pool of software engineers. "We're in the best place in the world for that," he says, adding that it goes with Tesla's insurgent approach. Whereas the established car companies tend to approach car design "with a deep comfort with internal combustion engines and a deep skepticism of software and electricity, we're the opposite."

Still, even if a Tesla proves itself as both simpler and more sophisticated than a conventional car, there's plenty that can go awry. Musk tells me he thinks the Model S has already made it over the most difficult hurdles. But it is hard to say for sure. "What could go wrong?" says Adam Jonas, an auto analyst at Morgan Stanley. "New technology, new factory, new manufacturing techniques, new company, new distribution channels--there are very few things here that aren't new." Jonas actually sees a bright future for the company, but he acknowledges that the road ahead will be difficult. And for Tesla, he adds, the bar is set extraordinarily high.

To Musk, the conventional thinking about the EV market is one reason why so many people fail to grasp Tesla Motors' potential. At the moment, fewer than 13 million cars and small trucks are sold in the U.S. each year. About 2% of those are pure electrics or hybrids. The accepted wisdom, Musk argues, is that "there's a market for electric cars and all electric cars compete against each other for that market. But that's just the wrong paradigm." Musk does not believe the Model S or X will compete with other EVs for dominion over a tiny slice of the consumer market. Models S and X will instead compete with gas-burning BMWs and Lexuses. And because Musk is assured his EV technology will prove superior in performance (and emissions), it will thus succeed.

Over the course of several years, Tesla sold about 2,400 Roadster sports cars. The company is planning to produce about 6,000 Model S cars this year, but next year it intends to scale up to 20,000. These numbers are not large for a big carmaker--Toyota sells more Camrys in a month than Tesla plans to sell in a year. Still, for an automotive startup, they seem heroic. But most of the auto analysts I spoke with think Tesla's sales projections are still far too high, a belief reinforced by modest sales figures for the Leaf and Chevy Volt. "Is 20,000 in sales optimistic? That's the billion-dollar question," says Brett Smith, a codirector at the Center for Automotive Research in Detroit. "I think there is a market for Tesla's product, but I don't know how large that segment is. And frankly I'm not sure it's as large as they hope." When I talked with Bob Lutz, the former GM vice chairman who spearheaded the development of the Volt, he told me he believes the Model S, which he considers a striking design, will be a success. He is less certain about the sales numbers or Tesla's long-term success. And he doubts the company is doing anything in terms of technology that the bigger carmakers couldn't do if they decided to enter the EV market with gusto. But Lutz doubts that will happen soon. "Look, neither the Nissan Leaf nor the Chevy Volt are being yanked out of the hands of producers by eager consumers," he admits. "The media might have you believe, Gosh, in 10 years it's all going to be EVs. But it's just not happening. The average American consumer is delighted with gasoline vehicles and is in no rush to change."

Not long ago, I spoke with Paul Scott, a longtime EV advocate who now works selling Nissan Leafs in downtown Los Angeles. The demand for the Leaf through 2011, he said, "was just outstanding." Scott sold nearly 200. But then Leaf production caught up with demand and what Scott perceives to be an initial group of early adopters all received their vehicles. "Then January came," Scott says, "and I didn't sell a single car the entire month."

The EV market remains enigmatic. And future sales may depend less on performance--or environmentalism--than on economics. At the moment, what's actually driving EV sales is government policy. Car companies, with their sights set on meeting high-mileage and low-emissions requirements for their fleets, view electric and hybrid vehicles as crucial to their vehicle portfolio. At the same time, customer rebates of up to $7,500 from the federal government and up to $2,500 from the state of California bring these cars into the realm of affordability. Yet two other factors shift the equation: The price of gas, though climbing, has remained fairly low over the past year, and the price of lithium-ion batteries is fairly high. By the calculations of Menahem Anderman, arguably the country's leading lithium-ion battery analyst, gas would have to be about $10 a gallon to recoup the lifetime cost of an EV like the Leaf. Anderman believes the economics look far better for the new plug-in Toyota Prius--$6 gas makes it a sensible economic proposition. In sum, his firm projects that the global EV market in 2015 will be quite modest in size (250,000 in sales) and will be dominated by Japanese and German automakers. Tesla, in his estimation, would be lucky to sell 15,000 cars.

He might be wrong, of course. A number of car analysts have far rosier projections for Tesla. And in any event, Tesla's Model S presents a confusing test case. It's a stylish, high-performance car, with a battery pack that gives it greater range (between 160 and 300 miles before recharging, depending on the model) than any other electric car. And EVs like Tesla's seem to be evolving at an astonishing rate. Straubel, Tesla's CTO, has little doubt that EVs will soon become competitive, even without incentives, with gas cars. "There's no fundamental law in physics that says you can't make batteries with much higher energy density and much lower costs," he tells me. By Straubel's calculations, if batteries get 50% better, it will put EVs on an even playing field with gas cars. "Between the time we did Roadster and Model S, the batteries have improved by about 40%," he says. "That's a pretty big number. That's about four years. And if that same thing happens with Model S, you could have an upgrade battery pack that's half the size in five years than what it is today." Such leaps are unheard of in car technology, he adds. "Engines don't drop in size by half in a few years. It doesn't happen. It's almost like the properties of steel are changing year by year."

This line of sight gives Straubel and Musk faith in their business model. But they're also buoyed by customer enthusiasm, which may be telling skeptics something the economic models can't. When I ask Musk if it's possible that Tesla could fail to sell 20,000 Model S cars annually, he says that it already has more than 8,000 preorders. And Tesla does not advertise, does not give discounts, and has never given any test-drives. Word has spread virally.

"So we're in the wrong sort of reference frame," Musk adds. "We're sold out--I mean, we're sold out until February of next year. I haven't checked the latest numbers. We might be sold out until March. So clearly we do not yet have any kind of demand problem. In fact, our problem is one of supply. Therefore our focus needs to be--and it is--on producing the Model S, bringing it to market as soon as we can." I ask if it is likely that once he exhausts the first pool of early buyers he will find demand evaporate, just as Paul Scott discovered with his Nissan Leafs. "Our Model S reservations have been accelerating," Musk counters. "If you want a Model S, don't think you can just wait and pick one up. The time is getting longer, not shorter, to buy one."

One afternoon in California, I make a visit to the Tesla factory in Fremont, about 30 minutes northeast of the company's HQ. For years, the factory was operated jointly by Toyota and GM; it was known as NUMMI (New United Motor Manufacturing Inc.). Tesla bought most of the factory buildings in 2010 for $42 million--the equivalent of pennies on the dollar. With the help of a $465 million federal loan (another example of federal policy nurturing the fledgling EV industry), the company began a strenuous effort to rehabilitate the old space. When I visit the plant, the final beta versions of the Model S are making their way through a gleaming new assembly area. When it's up to speed, the factory should turn out 80 a day.

If there are any suspicions that Tesla has more modest ambitions than it lets on, a visit to the 5.5-million-square-foot plant will quickly dispel them. "Elon wants to fill up this factory," Gilbert Passin, Tesla's VP of manufacturing, tells me during a tour. Passin, a native of France and a manufacturing wizard who spent his career at Toyota and Volvo, is driving us around in a golf cart. The plant is almost too large to walk through; we go past the production lines, the tool dies and presses, the plastic molding shop, in and out of buildings, and on and on for what seems like miles. "This factory was capable of producing a half-million vehicles by NUMMI," Passin explains. "We obviously are starting with a modest contribution of 20,000 a year. But we have all this, all these buildings." By Passin's estimate, Tesla now takes up about 15% of the factory, most of which remains grimy and locked up.

In many respects, the Tesla plant is not a traditional car factory. "You have to understand," Passin says, "with a fraction of the cost of what others would spend, and a fraction of the time, and a fraction of the resources, we are trying to do something really kick-ass." Building a different kind of car technology means you can build it in a different way, and possibly much more efficiently. At the factory, the large Tesla battery packs are assembled on the second floor and are eventually joined with the car chassis and bodies on the ground floor. But the chassis move along not on an automated assembly line but on bright red robotic carts that follow a magnetic strip on the concrete floor. Everything is electric. When a Tesla Model S is complete, in fact, you can actually test-drive the car on a bumpy road built within the factory. (The cars have no tailpipe or emissions, making them indoor-friendly.) Passin also points out to me that Tesla is trying to avoid using outside suppliers for parts whenever possible. The company, moreover, has the highly unusual intention to make its own dies to stamp sheet metal to its own specifications. "If you master that," he tells me, "you master the know-how that goes along with it." As he puts it, "We want to do everything ourselves."

This may explain why there's a lot of chatter in Silicon Valley about whether Tesla can be the next Apple. Of course, designing a physical product and producing it in a vertically controlled manner doesn't mean you're the next Apple. There are nevertheless similarities. Tesla is in the process of building a network of elegant stores in affluent areas (all of them overseen, incidentally, by George Blankenship, an Apple retail veteran). And there seems a conceptual kinship in the way Tesla is trying to bring an innovative, stylish design to market: by starting at a high luxury price point and then moving toward mass production, just as Musk's master plan said it would. In certain respects this diverges from how other upstart auto companies gained a foothold. Toyota and Honda put down roots in the U.S. market by offering cheap cars with high gas mileage that caught consumers' interest during the early 1970s gas crisis.

Musk doesn't push the Apple comparisons, but he sees them as a useful point for debate. "The only strategy that could have been successful," he tells me, "was the one we employed, which was to start out at low volume but with a high-priced car. Because we didn't have a billion-dollar factory. There are really two things that have to occur in order for a new technology to be affordable to the mass market. One is you need economies of scale. The other is you need to iterate on the design. You need to go through a few versions." If it were possible for Tesla to have made a mass-market car from day one, he continues, "that is the car I would have made. That is the car I've always wanted to make." Yet by Musk's estimation, he needs at least three major versions of his automobile before he gets to what might be called his iPhone. "Think of Windows 1, 2, and 3," he says. "Do you even remember 1 and 2? Or look at Apple. They had the Apple I, the Apple II--and the Mac. That's what you need to do."

Musk has no doubts he will get there. Neither does Passin, who seems to look around his quiet factory and not see it as it is--a huge, dark complex that swallows up the tiny and valiant Tesla effort--but as it could be. "Two years ago, there was no manufacturing team, there was no plant, I was by myself, and Elon Musk said, 'You have two years to create a manufacturing team, find a plant, and build a vehicle that beats all the others.'" He was at Toyota, arguably the world's best car manufacturer. Why sign on to such a risky endeavor? "To be part of history," he says in accented English, as he parks the cart he's driving to face me. "How many times in your career have you been told, 'Go create your own team, your own plant, your own process--from scratch?' How many times in your career do you get to do that? And it's an electric car, which no one else has done. And it's going to be a premium sedan, which everyone is going to want. And, and, and, and. How many times are you going to have this opportunity? Zero." He pauses to gather his thoughts. "I mean, I'm lucky I have this opportunity at all."

Passin starts the cart and we drive the long length of the factory toward the exit. It's getting late; only a few workers remain. The sun is streaming into the enormous room through the factory's clerestory windows. It's bouncing off the floor's glossy white epoxy and reflecting off the welding robots, more than I can count, all painted a bright and shiny Tesla red. In just a few weeks, production will start in earnest and sparks will be flying everywhere. But for the moment, at least, the factory is immaculate, poised for action, a place of pure possibility.

tesla Model S: the double threat It's an electric car competing as a luxury sedan. How does it compare in both worlds?

PRICE*

0-to-60 TIME

RANGE/MPG EQUIVALENT

TESLA MODELS

$49,900

6.5 seconds

160 MIles/119 MPGE**

Electric Vehicles

Nissan Leaf

$27,700

10.3 Seconds

100 miles/99 MPGE

Chevrolet Volt (hybrid)

$31,645

9 seconds

35 miles/94 MPGE

Mitsubishi Miev

$21,625

13.4 Seconds

62 miles/112 MPGE

Fisker Karma (hybrid)

$95,900

6.3 Seconds

50 miles/52 MPGE

Luxury Sedans

Audi A7

$59,250

5.4 seconds

18 City/28 Highway

Cadillac CTS-V

$64,515

3.9 seconds

14 City/19 Highway

Mercedes Benz E350

$50,490

6.5 Seconds

20 City/30 Highway

Jaguar XF Sedan

$53,000

5.5 Seconds

16 City/23 Highway

*Price after federal rebate. **Miles-per-gallon equivalent for Tesla Roadster; Tesla has yet to release MPG for the Model S, but it's likely similar. Leaf 0-to-60 time from consumer reports. Miev 0-to-60 time from motor trend. No manufacturer stats available.A version of this article appears in the April 2012 issue of Fast Company

re-examining the reputation and aesthetic of bamboo through a contemporary interpretation of the all-time western classic windsor chair, the design is the winner of the 'home interiors' category of the TIFF award 2012.

Businesses’ energy intensity – measured by kWh per square foot – declined by 8 percent from Q1 2009 to Q3 2011, according to customer data from energy management company Ecova. Big box retailers, those with floor space of 25,000 square feet or more, saw their energy intensity fall by 10 percent over that time period, [...]

Businesses’ energy intensity – measured by kWh per square foot – declined by 8 percent from Q1 2009 to Q3 2011, according to customer data from energy management company Ecova. Big box retailers, those with floor space of 25,000 square feet or more, saw their energy intensity fall by 10 percent over that time period, [...]

Comments by our Users

Be the first to write a comment for this item.